In a new report launched today, Open the Doors! Towards Complete Freedom of Movement for Human Rights Defenders in Exile in Uganda, DefendDefenders examines freedom of movement of exiled human rights defenders (HRDs) in Uganda. Due to Uganda’s ‘open-door policy’, Kampala acts as a hub city for exiled HRDs seeking respite and safety.

“The publication of this report coincides with DefendDefenders 15-year anniversary, marking a decade and a half of support to HRDs in some of the most difficult points of their lives. It is poignant that this report is a testament to the openness and welcoming nature of Uganda and the Ugandan people – who have themselves hosted us for 15 years,” says Hassan Shire, Executive Director of DefendDefenders.

While moving freely into and within the country is relatively easy, moving out of Uganda can be difficult for exiled HRDs. As most of them remain in Uganda with refugee status, they often do not have the necessary documents to travel internationally. The report demonstrates HRDs’ resourcefulness and resilience in navigating frustrating and sometimes non-transparent systems to be able to carry out all aspects of their work, including travel abroad.

The report presents recommendations to the governments, international organisations, and civil society. It also serves as an educational tool for HRDs, sharing the experiences gathered by fellow HRDs who have successfully obtained travel documents and visas – we have compiled this information into a small brochure, outlining the process of obtaining a Convention Travel Document (CTD).

Executive summary

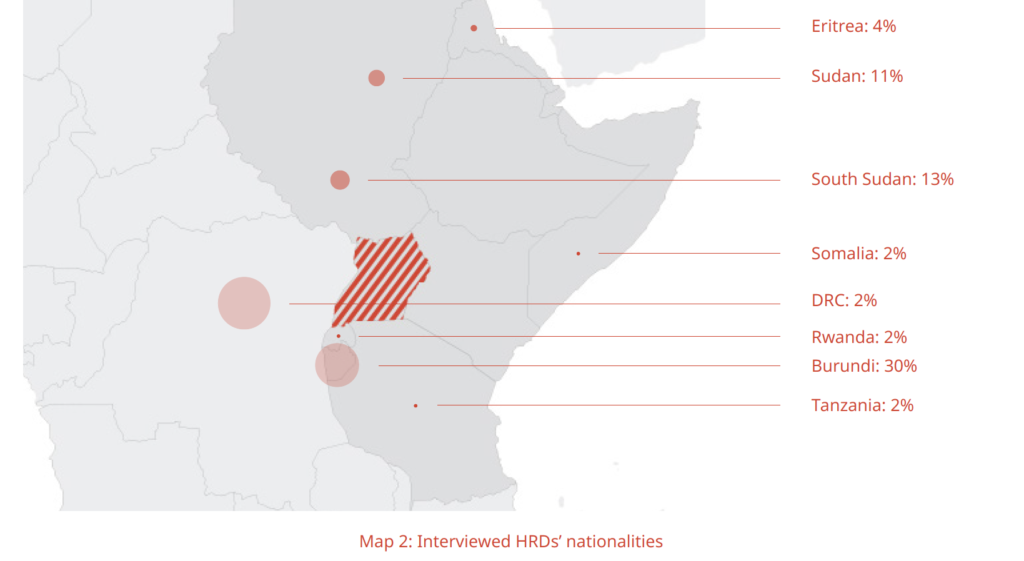

Uganda is a hub for migrants, asylum seekers, refugees and more specifically, HRDs, in the East and Horn of Africa sub-region. An HRD is anyone who individually or in association with others promotes or strives for the protection and realisation of human rights and fundamental freedoms at the national, regional, or international levels, using peaceful means. An HRD is defined as living in exile when barred or forced to leave, officially or in practice, from their home country, typically as a form of politically motivated punishment or as a result of threats. Uganda’s status as a relatively peaceful, open and accessible country, with a proclaimed ‘open-door policy’ for asylum-seekers and East Africans, has not only served to draw more HRDs towards Uganda but has also led to much discussion surrounding Uganda’s ‘model’ system. This includes the mostly positive international attention paid to the Ugandan refugee policy, which focuses on open borders and settlement, rather than camp living. The central role of Uganda in East Africa, both geographically and politically, and the history of East African leaders having sought refuge in Uganda and vice versa have arguably created a conscious state of ‘welcoming’ in the Ugandan psyche. This extends beyond HRDs or political leaders, to refugees and asylum-seekers more generally, who are largely able to benefit from Uganda’s liberal free movement policy.

Many of the HRDs who come to Uganda enter into the asylum/refugee system as soon as they arrive. Therefore, the experience of the average HRD in Uganda is inevitably linked with the refugee systems and processes of one of the largest refugee-hosting nations in the world. While this research began with asking the question of how free HRDs in Uganda are to move into, within, and out of Uganda, it quickly became clear that the question could not be answered without understanding and evaluating refugee systems in Uganda more generally. The main reason for this being that many HRDs are recognised as refugees in Uganda and remain in the country on the basis of their refugee status. Thus, their freedom of movement and other rights are governed by their status as a refugee primarily, not as an HRD or national of their country of origin.

The right to move freely into and within Uganda remains largely uncontested in theory and practice. It is reported to be upheld by both HRDs and those working on migration in Uganda. Yet, many HRDs face compounded issues, such as lack of money, concerns about their personal security, and denial of travel and movement permits due to being viewed as too politically active. These issues can prevent them from moving completely freely. However, the most serious issue for HRDs, concerning freedom of movement, arises when trying to leave Uganda to travel abroad. For HRDs who are recognised as refugees in Uganda, the process of traveling abroad is made all the more complicated by their status in Uganda, their inability to access or use passports delivered by their home country, and the complicated and often intimidating process to obtain a convention travel document (CTD) for refugees. Those who do possess a CTD often struggle to use it, as they face discrimination and profiling when applying for visas and find that even invitations to attend official events are not guarantees that their applications will not ultimately be rejected.

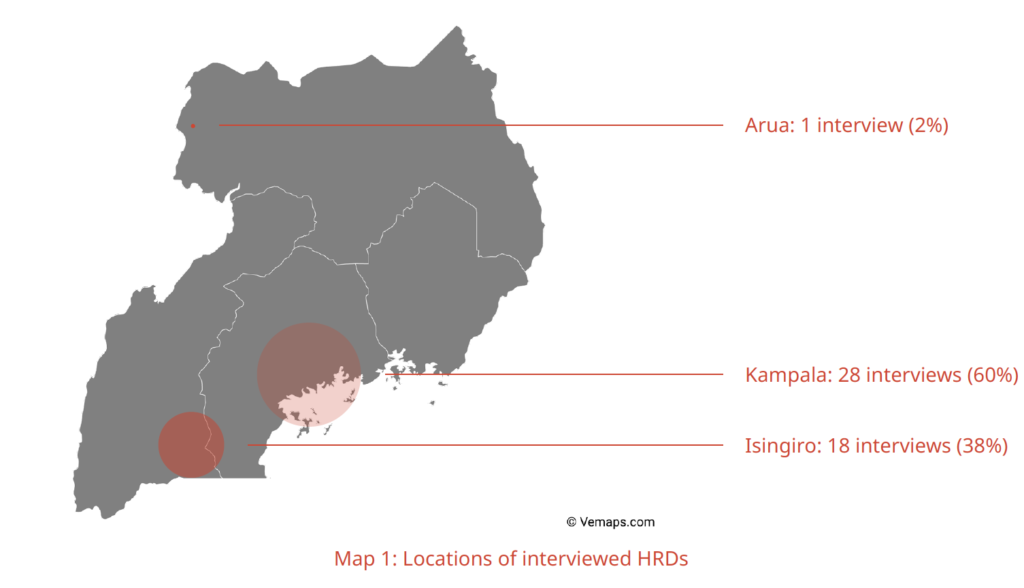

Based on a total of 53 interviews with 47 HRDs living in exile in Uganda and 6 key informants working on related issues in the country, this report delves into the difficulties and concerns that HRDs have in relation to the exercise of their right to freedom of movement. It highlights the challenges that many HRDs face when living in protracted exile and is an illustration of the wider struggle that refugees meet when stuck in limbo – living without the same benefits as nationals and having been forced to rescind entitlements from their home country. It demonstrates the resourcefulness and resilience of HRDs in exile in Uganda, but also highlights the complicated, frustrating and sometimes non-transparent systems that they must navigate in order to be able to carry out necessary components of their work that are often taken for granted by persons not living in exile. In addition, the report serves as an educational tool for HRDs, to navigate through some of these systems, as they can benefit from the experience gathered by fellow HRDs who have successfully obtained travel documents and visas.