As wide as the Atlantic?

Reflections on the New York/Geneva gap and the place of the UN’s human rights pillar

This year, DefendDefenders travelled to New York to attend the High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF 2023). The meeting, organized under the auspices of the United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), took place at the UN headquarters. Like every four years, an SDG Summit will also take place in September 2023.

We are grateful for the opportunity and thank partners, including Brot für die Welt (Bread for the World), the NGO Major Group, Action for Sustainable Development, CIVICUS, and the Hawai’i Institute for Human Rights, for helping us navigate the HLPF.

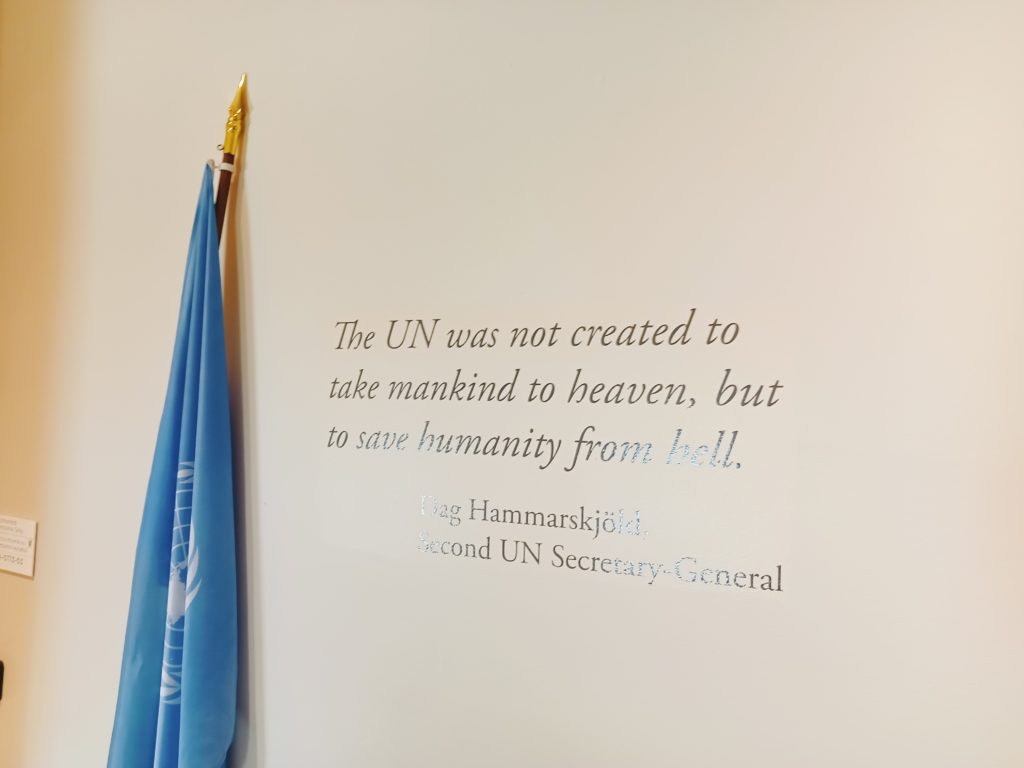

“Navigating” aptly describes what HLPF engagement means. UN New York and UN Geneva are two different worlds, and civil society organisations that are used to advocacy in Geneva face a wholly different environment when they cross the Atlantic Ocean.

New York: so close, yet so far

DefendDefenders has a long history of engagement with the ECOSOC. As the founder of the East and Horn of Africa Human Rights Defenders Project, our Executive Director, Hassan Shire, appeared before the NGO Committee of the ECOSOC – the body that reviews NGO applications for consultative status with the UN. This is a sine qua non for organisations that seek official recognition by the UN. Without “ECOSOC status,” an organisation cannot deliver oral statements before UN bodies, for instance, or book rooms for parallel events within UN premises.

Our consultative status was officially approved in 2012. This was the end of a process that, for many human rights NGOs, is stressful, lengthy, and frustrating. Over the years, the NGO Committee has become overly restrictive, effectively blocking the participation of many independent human rights NGOs.

In practice, as for our human rights counterparts, once our ECOSOC status was approved, we focused on engagement with the UN human rights system. This means Geneva, not New York. For human rights NGOs that seek to engage with the UN, New York is a prerequisite, but there is no obligation to maintain an office in the Big Apple.

Civil society space: New York vs. Geneva

For those who are used to Geneva, in particular the UN Human Rights Council (HRC), New York comes as a shock.

Indeed, within the UN family, the HRC is unique insofar as it provides significant space to civil society. At the HRC, we, NGOs, have the ability to, among others:

- Present written submissions (not just official UPR submissions but also advocacy letters and written statements to the HRC – see an example here);

- Organise parallel events (known as “side events” – again: an example at the last HRC session);

- Deliver oral statements at a range of debates and events (NGOs’ speaking time at the HRC is unrivalled, although it has been reduced as a result of “efficiency” measures);

- Have access to state representatives, i.e., diplomats, including ambassadors (contacts are facilitated by the size of Geneva, which is 50 times smaller than New York, and facilities such as the famous “Serpentine Bar”); and

- Have access to negotiations on draft resolutions (“informals”).

These show how seriously civil society space is taken at UN Geneva and by the HRC. Other Geneva-based bodies and mechanisms also allow for NGO submissions, statements, and events. Treaty bodies’ practice of considering “shadow reports” by civil society, NGO briefings with Committee members, and special procedure consultations with civil society and human rights defenders (HRDs) are well-known. The Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) also widely consults with civil society.

Despite uncertainty over the long term, remote participation through hybrid modalities has also been possible since Covid-19. Video statements have become a feature of UN human rights bodies, allowing representatives of NGOs and grassroots movements to officially speak without travelling to Geneva.

By contrast, in New York, civil society space is restricted. For NGOs, moving from Geneva to New York is like moving from working in a kind, caring team to working under a malevolent, toxic manager. Among the changes: access to diplomats is uneasy, speaking slots are a rare commodity, and NGOs have to partner with states to hold side events. Like everyone else in New York, civil society advocates work in silos, in hyper-specialized niches. The gap between Geneva and New York is as wide as the Atlantic.

As multilateralism is under attack, Geneva is relevant

New York, however, remains the centre of multilateral politics. Several of the UN’s principal organs, namely the UN Security Council (UNSC), General Assembly (UNGA), Secretariat, and ECOSOC, are based there, as well as two of the UN’s three pillars (peace and security, and development). These are the two “well-funded” pillars, compared to the UN’s human rights pillar.

In many New York-based negotiations, consensus, or unanimity, is the rule. This means that to be approved, an outcome (resolution, statement, political declaration) must be endorsed by all states – or at least not opposed by any. This results in lengthy negotiations that risk leading to the “lowest common denominator” (Ministerial Declarations at the end of HLPFs or Political Declarations at the end of SDG Summits must enjoy consensus) or ending up in a stalemate (as when veto powers are used at the UNSC).

So, paralysis is always a risk. The current state of international affairs does not lead to optimism in this regard. Decision-making is more and more challenging (look at the UNSC’s failure to take any action on Sudan or to decisively act regarding conflicts in Syria, Yemen, or Ukraine), and multilateralism is under attack. Agreed language is challenged, veto powers are used for obstruction, and narratives on “state sovereignty” serve as excuses for non-cooperation and denial of humanitarian access.

On the other hand, the Geneva-based HRC has no obligation to act by consensus. No state has veto powers over Council resolutions, which means the Council acts even on difficult, geostrategically-charged situations. During its 17-year existence, the HRC has engaged in normative development and standard-setting, established investigative and accountability mechanisms, reviewed the human rights record of all countries (through the UPR), and addressed human rights crises by holding special sessions, including when New York was paralysed.

Egregious violators still sit as members of the HRC, but at least, the Council has the good taste of not letting them block resolutions. Geopolitical divisions are as clear in Geneva as they are in New York (including in debates on gender, sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR), and on all sovereignty-related issues), yet the HRC delivers – over 30 resolutions per session. Geneva is relevant.

From peace and security to sustainable development, human rights are central to the UN’s work

Yet Geneva seems to be at worst absent from New York thinking, and at best an afterthought in New York discussions. The sad reality is that the UN human rights system is not at the centre of everyday conversations at UN headquarters.

At HLPF 2023, we heard, time and again, that we need to accelerate implementation of the Agenda 2030/of the SDGs. We are indeed half-way between 2015 (when the Goals were adopted) and 2030.

But largely absent from HLPF 2023 discussions was precisely how to use human rights and civic space to accelerate implementation of the SDGs. Many of the SDGs are human rights at their core, and without respect for human rights, including the freedom to speak out, to monitor government action and to peacefully assemble to demand progress, the SDGs will not be achieved. In short, human rights, civic space, and sustainable development are intertwined. The same goes for the African version of Agenda 2030, namely Agenda 2063.

At DefendDefenders, we see the following as key action points:

- Human rights should be mainstreamed throughout the UN system, i.e., they should be part and parcel of discussions on peace and security and on sustainable development. There must be a human rights-based approach to the SDGs and beyond (just like, on the African continent, human rights must guide action on the Agenda 2063). The 2023 SDG Summit and the 2024 Summit of the Future should centre human rights and make sure they are more than an afterthought. Human rights are not just part of SDG16. They are key to the whole sustainable development agenda.

- Human rights discussions should be re-energised at the African level. The Africa We Want will never be a reality without respect for the human rights and fundamental freedoms of all African citizens. In this, Africa could even show the path to the UN by unequivocally centring human rights in its Agenda 2063.

- There must be concrete action on the UNSG’s Call to Action for Human Rights, which highlights that “[t]he 17 Sustainable Development Goals are underpinned by economic, civil, cultural, political and social rights” and that “[r]ealizing human rights […] requires broad and sustained engagement with states, civil society and other stakeholders, and is intrinsically linked to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.”

- Human rights should be considered in UN reform:

- At the very least, information-sharing should be improved between Geneva-based bodies such as the HRC or OHCHR and New York-based bodies, including the Security Council. This could be achieved by enhancing official channels of communication (presentation of reports, briefings by the High Commissioner and other human rights officials such as heads of human rights divisions of peace missions, as well as, on specific crises, special procedure mandate-holders). Unofficial channels could also be improved: it means, in many cases, simply paying more attention to outcomes of Geneva-based bodies.

- Ideally, UN reform will provide for the elevation of the HRC from the status of a UNGA subsidiary body to that of principal organ of the UN (the problem being, of course, the requirement of a P5 unanimity for amendments to the UN Charter…).

Irrespective, we come back from New York with the belief that compartmentalisation should end. New York should pay more attention to what’s going on in Geneva, and vice versa. The UN should also pay more attention to Africa’s own development agenda.

We remain committed to doing our part, making sure that the voices of African HRDs are considered in decision-making at the African and UN levels, including on peace and security and development issues. Without human rights, there will be no lasting peace. Without human rights, there will be no sustainable development.

Kampala/Geneva, July 2023