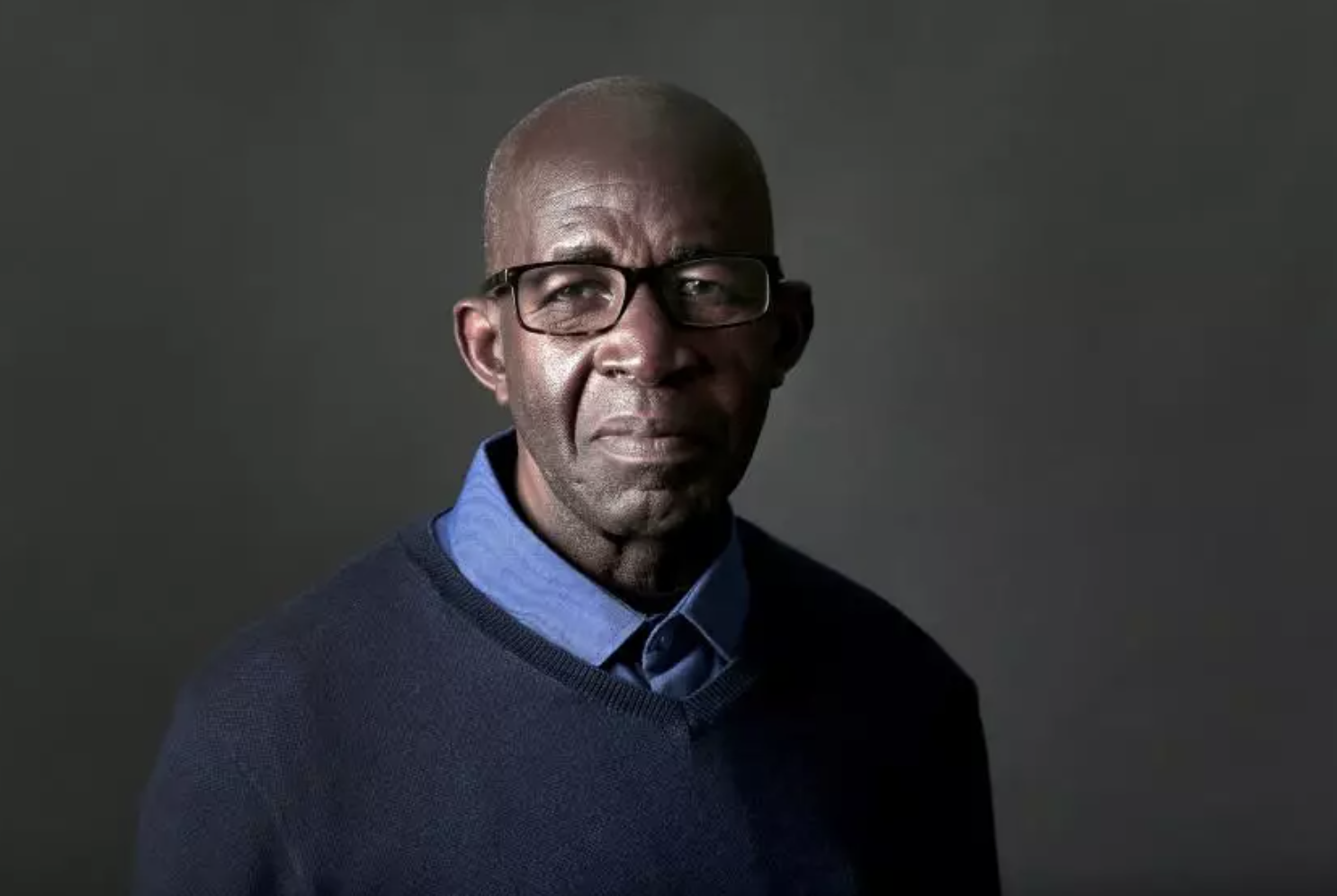

Arguably no single individual personifies Burundi’s human rights struggle like Pierre Claver Mbonimpa. Born 72 years ago in the small East African country, Claver’s quest for human rights and justice is as old as his country’s modern history.

When his country was plunged into a civil war that killed an estimated 300,000 people following the 1993 assassination of President Cyprien Ntaryamira, Claver was one of its earliest victims. Then a close confidant (he was also a former driver) of the assassinated President, he was framed, and arrested, and would go on to spend the next two years between 1994 and 1996 in jail.

It is in prison that the ulcer of injustice bit him hard. There, he met inmates who had either been wrongfully imprisoned or who had been remanded for long periods without trial, all living in dehumanising conditions. “I was strongly revolted by the injustice. Here were probably innocent people whose years were being wasted away by an unfair judicial system, with no one to stand up for them. I swore that I would try to do something about it once I got out myself,” he says.

He was freed in 1996, and immediately started the Association for Detained Persons (ABDP), through which he would move around prisons monitoring the welfare and wellbeing of inmates and mobilising legal representation for those without. His intervention was a massive success, and as friends and relatives started receiving their long-detained loved ones thanks to his intervention, he was encouraged to look beyond prisoners and advocate for human rights beyond the prisons.

“People with other issues like land conflicts, and other victims of injustice had started coming to me. But legally, my mandate was limited to advocacy for prisoners’ rights. So, if I was to be of help to other people, I had to expand my mandate,” he says.

Pierre Claver Mbonimpa Tweet

So, in 2001, he started the Association for Protection of Human Rights and Detained Persons (APRODH). With support from Amnesty International, APRODH opened branch offices in other provinces of Burundi and started sensitising locals about the Burundian Penal Code, criminal procedure, among others, to create a civically conscious citizenry. It also started monitoring, documenting and carrying out countrywide advocacy against human rights violations, thanks to their office presence in a good number of provinces.

“We also started training policemen and women on the lawful handling of prisoners, and where prisoners couldn’t afford legal representation, we would step in to pay their fees, whenever possible,” he says.

Pierre Claver Mbonimpa Tweet

But APRODH and Claver’s cordial ties with the government of then President Pierre Nkurunziza were not to last. As President Pierre Nkurunziza neared the end of his constitutional two terms in office, he planned to insist on a third term, and he approached Claver to support his quest, which the latter flatly declined. Then, in 2014, Claver, on a radio program, criticised the government’s recruitment and training of a youth para-military outfit – imbonerakure ahead of the country’s elections due the following year.

He was immediately arrested and released three months later due to international pressure on the Burundian government for his release, but his freedom was short-lived. On 3 August 2015, Claver was shot by a gun man in what was widely seen as a political assassination attempt. The bullets shattered his jaw, his voice glands and back vertebra, and Claver had to be airlifted to Belgium for specialised treatment, where he spent nearly two years without speaking and eight months without eating.

As if that was not enough, while he was away for treatment, Claver’s son and son-in-law were killed in quick succession by people widely believed to have been state agents, and Claver himself had to be put under 24/7 protection by Belgium security on his hospital bed. APRODH was consequently de-registered in 2016, and Claver had to relocate the remainder of his family to Belgium, where he remains a refugee, to date.

Despite all that life-threatening experience, Claver remains undeterred, and continues to monitor developments in Burundi, and to carry out international advocacy for human rights reform back home. He says he does it for those who cannot speak for themselves.

“At least for me, I was able to recover my voice. There are those who are voiceless. Someone must speak up for them,” he says.

Pierre Claver Mbonimpa Tweet